In Stock and Custom Order Handpans for sale

Domes, also known as dimples on hand pans, have been a source of curiosity and debate between builders and players alike. There is still mystery and some misunderstanding of their purpose and effect on the drum. Are they for looks? Do they serve a functional purpose? Are they a new development? Lately there have been a lot of questions and discussions about their purpose specifically on the hand pan, which has inspired us to further research the history of their origins and various uses in musical instruments as well as consider our own research on the topic. The following is commentary on some of the history that we have found as well as some of our thoughts on our experience designing dimples on the Saraz. This is in no way fully comprehensive or definitive. We contribute these ideas in hopes that it inspires more builders to share their own insights on dome architecture in a healthy exchange of knowledge that promotes camaraderie among the art form.

Since creating the Saraz in 2012 and with Josh’s experience tuning steel pans with flat notes for almost 2 years prior to joining the Saraz team, we have spent countless hours exploring a vast array of different dome architectures. Of the many aspects that play a huge role in controlling and shaping the timbre of the drums, the dome’s function continues to surprise us in many ways. Whether it is shaped to be oval, round, diamond, double stacked, triple stacked, quadruple stacked, smaller or larger, the experimentation and results of dome architecture and its effect are worthy of discussion. We will use the term “dome” instead of “dimple” here, though the term dimple has been commonly used in the hand pan world. First let us take a look at the history of the dome on a few different musical instruments.

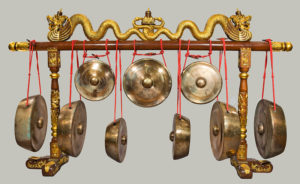

History of dome architecture of gongs

Of the many instruments made from steel and various metals, one of the oldest instruments is the gong. Said to have originated in China sometime during the 2nd Millennium BC, many still believe the gong had been around long before then. Chinese tradition says the gong originated in the country of Hsi Yu, and that by the 9th century had spread to Java, Indonesia, Malay and later on into Europe. The gong had an array of uses ranging from the mundane to the mystical. It was originally thought to bring good fortune and happiness, announce the presence of royalty, accompany religious rituals and feasts. Later on, more mundane uses like summoning workers, communication, and entertainment adopted the sounds of the gong. Some gongs were loud enough to be heard 50 miles away! There are generally 3 main types of gongs including suspended gongs, bowl gongs, and bossed or nippled gongs.

The dome on gongs is said to have originated by the Javanese, who started making all of their gongs with a bossed or nippled center. These gongs were tuned to specific frequency ranges used in Gamelan music, which is created by traditional Java or Bali based ensembles consisting mostly of percussion instruments. While tuning and building methods are hard to find or kept secret among top gong builders, these bossed or nippled gongs were consistently described as sounding warmer, softer, controlled, and less cymbal-like than the flat gong, known also as the Tam-Tam. They had a “wash” of sound instead of crash of sound. When listening to an audio clip, the sound difference between the two is quite distinct. Here is a great demonstration of the different gong types, with a whole section based on the bossed or nippled gongs. Some builders tune the bossed gongs to a definite pitch as well as a timbre that seems more controlled and direct as well as warm and soft, versus the brilliance and brightness of the more plate-like gong. The nippled portion of the bossed gong is stiff, and doesn’t resonate like the rest of the instrument.

Dome Architecture of Hand Bells

The dome on hand bell instruments has also played a large roll in timbre control. Two of the most prominent hand bell makers, Malmark and Schulmerich, spent years in court trying to prove who was making the best sounding hand bell and why. The hand bell traditionally has a little nub at the top, also known as the “tang”. This is where the handle is joined to the hand bell itself. After leaving Schulmerich, Jacob Malta had a vision of creating an even better sounding design than what he achieved with Schulmerich. After traveling the world and researching bell design and architecture, he returned and made one slight, but to him, large discovery. Removing the little dome at the top would provide a more “pure” tone than those with a tang on top. The debate was so heated that some of the lawsuits between the two companies ranged in the millions of dollars. At one point, an engineering team was assembled to prove whether or not a hand bell without a tang would be louder than one with a tang. After creating a robotic device that would hit each hand bell with the same exact precision, it was determined that the tang did make a hand bell louder by 1-2%. While no conclusive tests were done to determine the frequency generation and timbre differences, the loudness being measured may have been a small difference yet still proves there is an effect from domes in sonic architecture. Some hand bell players now discuss the differences of the two brands in terms of warmth and brightness which ultimately result from the influence of the tang.

History of Dome Architecture on the Steel Pan

Now, to get closer to understanding the dome’s effect on sound, let us explore the history of the steel pan prior to the development of the hand pan drum. As early as the 16th century, African slaves had been transported to the island of Trinidad to work the plantations owned by the French and Spanish. Years of depravity and struggle against the elite left the people tired, wary, and frustrated. Many had lost their native language. Music was one of the few ties left to their homeland. Having been rich in rhythm, the Africans started to explore drums that were metallic. Due to violence and unrest on the island, the elite slowly began to ban the congregation of musicians and even went as far as making it illegal for the slaves to have instruments. At this point with few instruments permitted to be played, people started to tap and bang on anything they could find including milk cans, car parts, metal pieces found in junkyards, and barrels from the Naval base nearby. Around the 1930’s, metal lids, tins, containers, etc had started to take shape into musical expression. Eventually bands would begin to form and they would take to the streets and march while playing and beating on whatever they could.

In the later 1930’s, a young musician named Winston “Spree” Simon was adjusting his barrel head, and noticed that the dent on it had a tonal quality. After thinking on it, he left and came back the next day having added 4 dents into the metal, generating 4 different tones. At the time, the pans were actually convex instead of the traditional “dish” like instrument we see today. Ellie Mannette was the first to “dish” the pan downwards and experiment with tone shapes, partials, and many other aspects of the steel drum. At the beginning, notes only had a single, fundamental tone. After years of experimentation from many different tuners, partials were added to the notes such as octaves, 5ths, minor/major thirds, etc. By the 1960’s, the violence on the island between musicians and locals was replaced by the large groups of steel bands that had joined together and would perform at Carnival, an event held on the Monday and Tuesday before Ash Wednesday in Trinidad and Tobago. Today, the steel pan is widely recognized by both musicians and non-musicians alike.

During the steel pan’s rise in popularity, it inspired people all over the world to take up the hammer and start creating their own steel pans. Among them, Felix Rohner and 4 members of the steel band “Bernese Oil Company” emerged to create “PANArt Steelpan-Manufaktur AG”. They were later joined by Sabina Sharer in 1995. During the years of Panart’s development, the company experimented with many things including adding domes to steel pan notes.

Dome Architecture and the Panart Hang®

With the turn of the century, Panart birthed the Hang ® which they say “came out of 25 years of manufacturing the steel pan and research on its technology and acoustics”. According to their article written in 2007 called “The History, Development, and Tuning of the Hang”, Panart also stated that “We began to study the vibration modes of gongs, bells, all kinds of drums, bars, plates and shells”. While it is hard to find much detail about the science behind the domes on metal instruments due to the secretive nature of many tuners and builders of gongs, it is clear that the gong along with its sound properties studied using laser rays and interferometry inspired Panart to adopt this ancient development and merge it with that of the steel pan. While they were not the only ones adding some form of the gong-inspired domes to steel pans, it was with the development of the Hang ® that the dome form became a topic of interest to the many people who were enamored with the new instrument. The top domed note of the Hang®, or “Ding” as called by Panart, was considered by Felix and Sabina to be “gong-like”.

Dome Development at Saraz

Since we at Saraz are not professional physicists or acoustic engineers, we are left with our own experience with the commonly termed “hand pan dimples”. Josh Rivera and Mark Garner started off learning to build hand pan drums by first exploring how to build steel pan variants without a dome on the center of the notes. These notes were still tuned with a fundamental, octave, and compound fifth. After building and learning to tune 153 notes this way, Josh was eager to move onto the next step in making a hand pan drum as we are visually familiar with by adding domes/dimples to the notes. His first experience was adding a dome to an already tuned note. As you might imagine if you have ever tuned a steel note, hammering in a dome to a tuned note will knock that note far out of tune. After working with it for a short while, Josh was able to bring the note back into tune however. He was also absolutely enamored and fascinated by the change in characteristic! Instantly, all of the descriptions used for the bossed gong sound came to mind. While he was a young and inexperienced tuner at the time, the change in timbre was shockingly definite. The words warm, controlled, soothing, and incredible were floating around in his head and he couldn’t stop hitting the note with the dome and then hitting the notes without them. While he didn’t have enough experience at the time to really understand what was happening, years later we have had numerous experiences with dome form architecture and experimentation surrounding it at Saraz. It is easy to speculate from our experience and the history of similar instruments why hand pan builders and the creators of the Hang ® use domes in their instruments. Why certain sizes and depths are favored likely depends on the experimentation and personal preferences of each builder.

So What do Note Domes actually Do?

When we hear the sound of the hand pan drum, we are hearing continuous vibration of the material pulsing through the air in waves. The timbre of the sound is made up of 3 main parameters: harmonic content, attack and delay, and vibrato. While there are many variables involved in the control of a hand pan’s timbre such as heat treatment, carbon content, types of metal, stability of the metal, forming methods, style of tuning, rust protecting oils and waxes used, we are here questioning what the purpose of the dome is.

Controlling Higher Harmonic Partials

What was Josh hearing when he first changed to domed notes on his early steel pans? Since the notes have a fundamental and also frequencies that are greater than the fundamental, there are also overtones created. An overtone is any frequency greater than the fundamental frequency of a sound. The fundamental and overtones combined create harmonic partials. Harmonic partials are considered more pleasing to most ears when the waves are created at integer multiple frequencies of the fundamental. In contrast, a less pleasing sound can be generated when an instrument creates disharmonious overtones in non-integer multiplications, which is also called dissonance. High quality instruments are usually built in ways to combat disharmonious overtones. An example is in brass instruments with the flared out ends. They are not flared to create a louder instrument. They are flared to correct the airflow of the long tubing, which can create disharmonious overtones. In traditional steel pan instruments, it has been desirable to create and achieve loud, bright, brilliant, and projecting overtones much like the original gong, which some wanted to build with the most dominating sound they could. Yet for some, the extra overtones were displeasing. Some builders were presumably looking to soften the timbre by dialing down the amplitude or eliminating some of the overtones created in order to only allow what was desirable to their ear. The Javanese discovered that the dome in the center of the gong seemed to attenuate and control those overtones and make it easier to tune and hear a specific tone. Felix’s research of gongs and the adaptation of Javanese-born bossed gongs into steel pans could likely have stemmed from the same Javanese goal to adjust and help control the overtones created by the steel pan.

Balancing Finger Strikes

One of the many differences that pertain to playing steel with your hands instead of sticks or mallets is the generation of frequencies from striking in places that steel pan players don’t strike. These include the edge of the notes, the interstitial (metal surrounding the notes), and in multiple areas on the note itself to activate select partials. It is common for steel pan players to get skilled at hitting the note with a mallet at the note’s sweet spot in order to generate the best sound. Steel pans tend to be built for this way of playing. How hard it is struck and how the instrument is built to handle the striking force plays a large role in the timbre. While skilled players have a good dynamic control, the hand has ten finger mallets of many different sizes and strengths. One effect of the dome on the center of a note is to help control the vibration caused by striking a note with more force. A hard strike can increase the amplitude and generation of overtones within a note. While a talented tuner and builder can create a balanced note without a dome to withstand the force of impact by using compression from the interstitial , the dome can make it easier to build strength and stability against such strikes based on its dimensions and relationship to the note while still opening up the note by eliminating the compression of the interstitial. The dome can also be used to more easily and consistently create balance of harmonic partials across all of the notes of an instrument. Additionally, the dome can influence the amplitude of specific partials based on the dome shape and depth.

Flat Membranes vs Spring Board Note Design

While the structural design of a note can be built and tuned in different ways that might be considered more like a flat membrane or more like a spring board, we have found in our experience after building notes in both ways that the dome has the same effect on the overtones and structural integrity of the note. Even the most flat well tuned hand pan note complete with a fundamental, octave and compound 5th still has 1-3 mm of elevation change that creates a hyperbolic paraboloid saddle shape (like a Pringles® potato chip).

Influencing Shoulder Tones

Another experience we have had is the dome’s ability to control the frequencies generated by the hand striking close to the edge of the note, which are often called the “shoulders” of the note. To some degree, the dimple is able to attenuate these frequencies, which tend to be heard on larger notes. Specifically, they seem to be more prominent on notes ranging from about D4 and down at least in our architecture and experience. An example of the unpleasing dissonance could be found on a B3 note. If the B3 is generating an overtone on the shoulder of the note in the frequency of G# 6 and the scale is a B minor, which has no G# in it, then this would sound dissonant with the scale. Furthermore, if the B3 is generating an overtone of F#6, which is in relationship to the 5th of the B3, it can become obnoxiously overbearing though technically in tune. Again, the dimple has the ability to move and or attenuate those frequencies to whatever the builder may desire.

Balancing the Fundamental and Harmonic Partials

This dome architecture will also have an impact on the balance of the fundamental and two main partials. On a hand pan drum, a commonly tuned note usually has a fundamental, an octave of the fundamental, and a compound 5th of the fundamental. This is specially important on the center note, which tends to commonly be the lowest note on the instrument though not always. The shoulders on the center note for our architecture are attenuated to a degree and can provide an extra element of play when tuned. Specifically, it can add a more percussion-like element. Various shaping methods, including dome architecture, can control the timbre of those tones and make them more pleasing.

Dome Generated Frequencies

Another interesting point is that as the dome itself gets bigger, it can become big enough to start generating its own frequencies. We have personally experimented with different sizes and shapes as well as stacking up to 4 domes on top of each other to see how to control these extra frequencies the dome sometimes will create. On the center note, the shape and depth of the dome can also add to the gong-like sounds generated by the Helmholtz resonator from the chamber and port on the bottom of the hand pan drum. While of course there are many variables, every experiment has proven to show that the dome, without question, has a large effect both in its ability and inability to control overtones and stability based on a builders architecture.

Dome Playing Techniques

Beyond the dome’s extensive influence on the sound, timbre and overtones of a note, it also offers new playing techniques that are not nearly as easily achieved without the angle and depth of a specifically shaped dimple. Here you can find an older Saraz video that shows exactly what we mean.

In Summary

With hand pans, the player may find their fingers and hands dancing over the entire surface of the steel thus forcing tuners to explore ways to tune and adjust all aspects of the steel. Just as the Javanese were exploring and evolving gongs and discovering the dome architecture, many steel pan tuners have explored and developed the sound design of the steel pan. In the history of mankind, sound exploration has been a constant evolution built upon and carried forward from the backs of those before us. The freedom and ability to take an instrument further than the ones before us and the ones before them has lead to a world rich with sonic character, musical diversity, and a language that transcends the native tongue as well as any single generation’s work. No one person owns the gong, the steel pan, flute, guitar, hand pan, piano, etc. These are all instruments whose development and evolution has been handed down to us from years of discovery and the freedom to share, explore, and create. Living in a time such as the birth of a new and beloved instrument is an incredible treat and honor for us all! We look very forward to seeing the continuing development of the hand pan. We would like to personally thank all of the gong, hand bell and steel pan builders as well as Panart for their hard earned contributions to the development of singing steel. Hundreds of years of development have resulted in the current chapter of what we now call the Hand pan. It is an incredible honor to have witnessed its birth, explore its evolution, and humbly observe as it continues to change so many people’s lives.

References:

The book, “hang: Sound Sculpture” Published by PANArt Hang Manufacturing Ltd. 2013

http://www.polearmball.com/The-Gong–Its-Lore–Its-History.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gong

http://www.pmgongs.com/gong-or-tam-tam.htm

http://artdrum.com/GONG_HISTORY.HTM

http://www.npr.org/sections/money/2013/12/23/256568061/the-great-handbell-war

http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/Sound/timbre.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Overtone

Working with Gongs#2 A guide to Gong types